“The Thomas origin of Christianity in the Dravidian South was the outcome of the missionary schema against Hindu religion and culture.” – Prof C.I. Issac

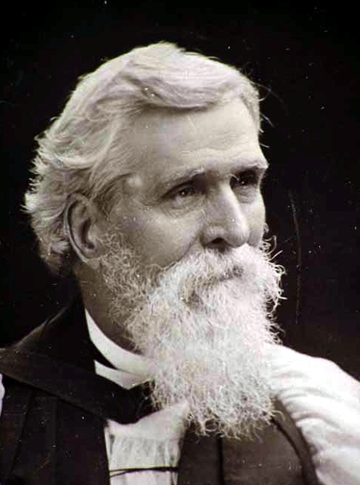

Speech by Prof. C.I. Issac, Former Head of Department of History, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, Kerala, on the occasion of the release of the book Breaking India by Rajiv Malhotra and Aravindan Neelakandan, in Chennai on February 3, 2011.

First of all I would like to congratulate Mr. Rajiv Malhotra and Mr. Aravindan Neelakandan for their painstaking endeavour of the book Breaking India. Most of our intellectual community conveniently bypasses the contemporary realities that are chasing the Hindu society in their mother land.

The respected authors of Breaking India have shown enough courage to unwrap the vanity of the pseudo-secularist and democrats of contemporary India. The book gives us a thumbnail picture of how far the missionaries misused the word “dravida” and “arya” in order to balkanise and Christianise India since the days of British Raj.

The fabrication of South Indian history is being carried out on an immense scale with the explicit goal of constructing a Dravidian identity that is distinct from that of the rest of India. It is factual that term dravida is derived from the Greek tongue. They used dhamir and dhamarike respectively for Tamil and Tamizakaom. Similarly they introduced our arasi and inchi in the West as rice and ginger.

But Bishop Caldwell, with his missionary zeal, misused the Greek derivative of Tamil and Tamizakaom and had given an anthropological representation. It was started in the 19th century with specific designs.

Suniti Kumar Chatterji (1890-1977), a renowned linguist, was of the opinion that Friedrich Max Muller, by the middle of 19th century, introduced Aryan-Dravidian dichotomy. Subsequently Bishop Robert Caldwell (1814-1891) followed the same foot-steps and in 1856 published the book A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South Indian Family of Languages.

This book epitomised distinctive anthropological status to the South and pictured as linguistically separate from the rest of India with an un-Indian culture. There is no definite philological and linguistic basis for asserting unilaterally the term dravida. His work was influenced with the defunct Aryan-Dravidian race theories proposed by Max Muller the German linguist. Thereupon the term dravida became the name of the family of a language.

During the early days of Common Era (CE) Greeks used dhamir / damarike for Tamil / Tamizakaom. Ancient Sri Lankans used dhamizha for Tamil. Sanskrit also used dramida / dravida for Tamil long before the birth of Common Era, probably between 1500 to 1000 BCE.

Brahmins of India broadly divided themselves into two groups Pancha Gauda (Gaudam / Bengal, Saraswatam, Kanyakubjam, Utkalam, Kashmeeram) and Pancha Dravida (Gurjara, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra, Dravida includes Kerala and Tamilnadu). Thus it has no anthropological base (Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Dravidian, Annamalai Nagar, 1965, passim).

In the light of the said Aryan-Dravidian dichotomy it is better to make an enquiry into the contemporary attempts to transform Tamil identity into the Dravidian Christianity. The advocates of this venture are striving to baptize Saint Thiruvalluvar through re-writing history. For instance Chennai Archbishop Arulappa once hired Ganesh Iyer alias Acharya Paul for re-writing the history with the said end. Such vicious endeavours targets to transform even Saint Thiruvalluvar, the pride of Mother India, as the disciple of Saint Thomas. (Anyhow their rationality failed to depict Saint Thiruvalluvar as the disciple of Jesus).

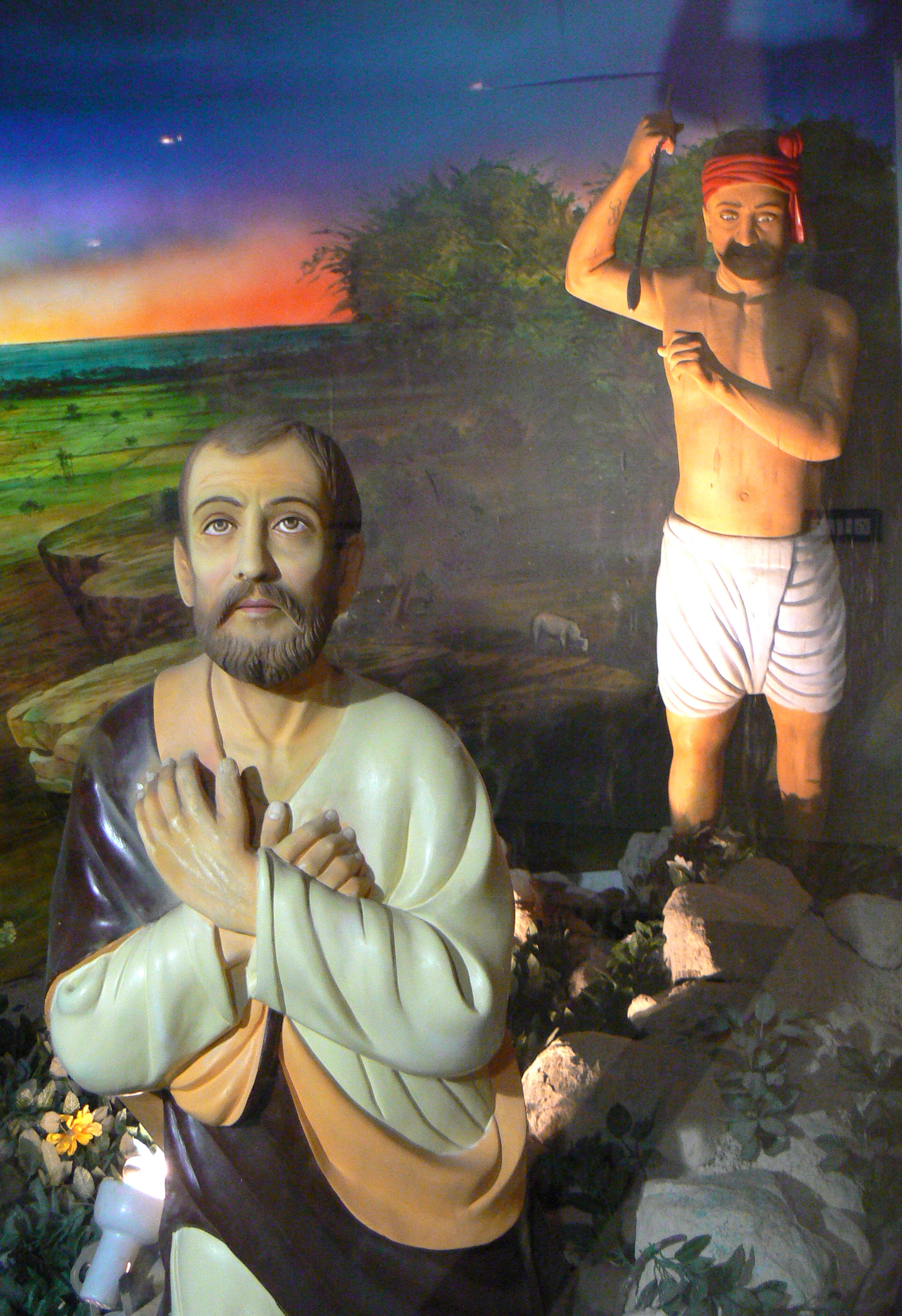

They are reducing Saint Thiruvalluvar’s greatness by making him as the disciple of Thomas who never visited India. Thomas’s mission to India is rejected even by Vatican also. Thus, I think, it is genuine to peep into the futility of apostolic origin of the Indian Christianity.

First question to be discussed here is the question of the arrival of Saint Thomas and subsequent conversion of Hindu aristocracy, particularly the Namboodiris / Brahmins, to Christianity.

Second one is the date of the question of the origin of Christianity in Kerala, the gateway of Christianity to India.

Third is the European interest behind popularisation of generating aristocratic (savarna) feeling among the native Christians.

Before the arrival of Europeans in India, a nominal Christian presence was seen only in the Travancore and Cochin regions of Kerala. According to Ward and Conner, even after two centuries of the birth of Christianity, the number of Christians on the Malabar Coast shrank to eight families (Ward and Conner, The Survey of Travancore and Cochin States, Trivandrum, 1863, p. 146).

The antagonism that was generated amongst the Christians and Muslims due to the Crusades of 11th, 12th and 13th centuries prevented Christians from planting their roots in the Malabar region where Muslims got roots quite earlier.

The Christian population altogether in Travancore and Cochin during the early decades of the 19th century CE was 35,000 with 55 churches (Ward and Connor, The Survey of Travancore and Cochin States, Trivandrum, 1863, pp. 146 & 147).

C.M. Augur says that from the arrival of Portuguese till the early decades of the nineteenth century here in Kerala there were only less than 300 Christian churches for of all the denominations (C.M. Agur, Church History of Travancore, Kottayam, 1902, pp. 7, 8, 9).

G.T. Mackenzie observes, Christians prior to the arrival of Portuguese, did not form the part of Travancore aristocracy (G.T. Mackenzie, Christianity in Travancore, Govt. Press, Trivandrum, 1901, p. 8).

Pope Nicolas IV sent John of Montecorvino, a missionary to convert India and China into Christianity and thus he wrote to pope in 1306 that “There are very few Christians and Jews (in India) and they are of little weight”. (See G.T. Mackenzie, Christianity in Travancore, Govt. Press, Trivandrum, 1901, p. 8). Cosmas Indicopleustes comments that Christians are not masters but slaves (N.K. Jose, Aadima Kerala Christavar, Vechoor-Vaikom, 1972, p 127).

The centre of the present savarna feeling of Syrian Christians of Kerala is the upshot of the wealth, which they had acquired through enhanced spice trade of the European period and the Portuguese pre-eminence in the Church. Above all the Christian-Muslim antagonism of West Asia was the real cause of the birth of Christianity of Kerala as seen today. To escape from the Muslim persecution of several Persian, Syrian, etc. regions, Christians secured refuge in India and thus it resulted in the birth of Christianity here. It is evident from the above mentioned pre-European period Christian-Muslim settlement pattern of Kerala.

In 1816 CE there were, in the Travancore State (now the part of Kerala), 19,524 temples and 301 churches for all denominations. But in 1891, that is after 76 years, the number of temples had shrunk in to 9,364 and the number of churches had burgeoned to 1,116 (C.M. Agur, Church History of Travancore, Kottayam, 1902, pp. 7, 8, 9).

Under the recommendation of Diwan Col. John Munroe, a British subject, in 1812 Queen of Travancore nationalized 378 wealthy temples. The villain Diwan tactically awarded a natural death to the temples with insufficient resources. Considering the geographical area, the number of the temples set ablaze or knocked down or tactically buried down in Travancore was proportionately much higher than that of temples demolished by the Muslim rulers of North India or Mysore Sultans.

In the year 1952 CE, the native Catholic Church approached the Papacy in Rome for pontifical approval to celebrate 1900th year of proselytism of Thomas. The Papacy declined the request of the Kerala Catholics on the ground that the claim has no historicity. Pope Benedict XVI had also declined the Thomas’s arrival and mission in the peninsular India. Only after the Portuguese Christianity in the South became a notable religious sect.

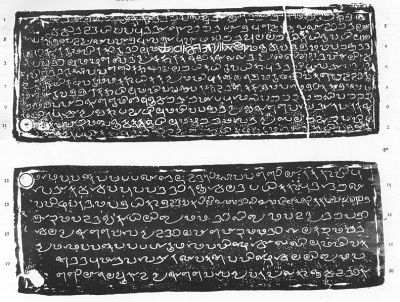

St. Theresa Church Copper Plate Grant (Terisapalli Cheppedu) executed in 849 CE by Ayyan Atikal Tiruvatikal of Venadu during the reign of Emperor Sthanu Ravi (844-855) is the available oldest historical document linking to Christianity of Kerala. That the grant holders were not native Christians is a notable fact.

Kottayam is the Rome of India. First church of Kottayam (Valiyapalli or Big Church) was built by a Hindu raja (Thekkumkur dynasty) in 1550 CE for the Persian Christian merchants (Knanaya Christians) who settled here (A. Sreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History, Kottayam, 1970, p 43).

The quality of missionaries to India until early British period was also remarkably very low. Missionary urge for Christianisation of India was fermented in England long before the 1813 Charter Act. In 1793 William Carey reached in Bengal, at Serampore, with missionary spirit without proper permission from the Company. Originally he was a cobbler by profession and turned out to be a Baptist missionary and became instrumental to the general missionary spirit that prevailed over England during this period (R. C. Majumdar & Others, An Advanced History of India, Madras, rpt. 1970, pp. 810, 811).

It is the fact that several of the much applauded missionary families of the colonial period were failed business men or opportunity seekers.

Christian population became decisive power only after the European intervention in the socio-economic structure of Kerala. Robert De Nobili, an early 17th century Catholic missionary of India, who lived in the attire of a Hindu hermit and established a monastery in Madurai to convert Brahmins. His attempt was to present Christianity in India as an aristocratic and Vedic offshoot. Thus the Thomas origin of Christianity in the Dravidian South was the outcome of the missionary schema against Hindu religion and culture.

The construction of Dravidian identity and induction of Saint Thomas myth is a calculated affair by the European Church which is now facing the extinction syndrome. The fragility of Christian base in the West is a well attested factor. In this changing scenario the Church cast its eyes in the third millennium over a highly spiritualistic society, the Hindu, for its survival. To a certain extent missionaries of the South succeeded to construct and politicise the Dravidian illusion. The need of the hour is to prepare the society to counter all such disguised and overt anti-Hindu accomplishments.

Note

See the comment below regarding the origin of the Terisapalli Cheppedu Copper Plate Grant.

The Terisapalli Cheppedu copper plates and what Claudius Buchanan noted – K.V. Ramakrishna Rao

To explain and expose the position of doubting and doubtful Thomas and his researchers in India, the following example is cited just for illustrative purposes. As the Kerala Christians make much fuss about the copper plates, what Claudius Buchanan recorded about them are noted here. They are as follows:

“But there are other ancient documents in Malabar, not less interesting than the Syrian Manuscripts. The old Portuguese historians relate, that soon after the arrival of their countrymen in India, about 300 years ago, the Syrian Bishop of Angamalee (the place where I now am) deposited in the Fort of Cochin, for safe custody, certain tablets of brass, on which were engraved rights of nobility, and other privileges granted by a Prince of a former age ; and that while these Tablets were under the charge of the Portuguese, they had been unaccountably lost, and were never after heard of. Adrian Moens, a Governor of Cochin, in 1770 who published some account of the Jews of Malabar, informs us that he used every means in his power, for many years, to obtain a sight of the famed Christian Plates; and was at length satisfied that they were irrecoverably lost, or rather, he adds, that they never existed. The Learned in general, and the Antiquarian in particular, will be glad to hear that these ancient Tablets have been recovered within this last month by the exertions of Lieutenant Colonel Macauley, the British Resident in Travancore, and are now officially deposited with that Officer.”

Copper plates script engraved later and none could read it in India

Buchanan continued,

“The Christian Tablets are six in number. They are composed of a mixed metal. The engraving on the largest plate is thirteen inches long, by about four broad. They are closely written, four of them on both sides of the plate, making in all eleven pages. On the plate reputed to be the oldest, there is writing perspicuously engraved in nail-headed or triangular-headed letters, resembling the Persepolitan or Babylonish. On the same plate there is writing in another character, which is supposed to have no affinity with any existing character in Hindoostan. The grant on this plate appears to be witnessed by four Jews of rank, whose names are distinctly engraved in an old Hebrew character, resembling the alphabet called the Palmyrene: and to each name is prefixed the title of ‘Alagen’, or Chief, as the Jews translated it.

“It may be doubted, whether there exist in the world many documents of so great length, which are of equal antiquity, and in such faultless preservation, as the Christian Tablets of Malabar.

“The Jews of Cochin indeed contest the palm of antiquity: for they also produce two Tablets, containing privileges granted at a remote period; of which they presented to me a Hebrew translation. As no person can be found in this country who is able to translate the Christian Tablets, I have directed an engraver at Cochin to execute a copper-plate facsimile of the whole, for the purpose of transmitting copies to the learned Societies in Asia and Europe. The Christian and Jewish plates together make fourteen pages. A copy was sent in the first instance to the Pundits of the Sanskrit College at Trichiar, by direction of the Rajah of Cochin; but they could not read the character.

“From this place I proceed to Cande-nad, to visit the Bishop once more before I return to Bengal.”

Analysis of Buchanan’s notings of the copper plates

A careful reading of Buchanan proves the following facts:

1. Even during 16th century, manufacturers of copper plate inscriptions were available.

2. They could manufacture the required copper plates even if they could not read the script they inscribed. In other words, they engrave as pictures and not as script or other details.

3. Who suddenly produced the copper plates for Buchanan is intriguing?

4. Buchanan made copies and circulated them for getting translation.

5. He also sent copies to London.

6. Original copper plates were not available.

7. Therefore, the Portuguese must have manufactured the copper plates.