“Macro Polo is the first writer in history to locate the tomb of St. Thomas on a seashore and by doing so he revolutionises the legend. All documents in the world prior to his locate the tomb on a mountain following the Acts of Thomas. Macro Polo is also the first writer in history to locate the tomb in South India. He wrote, “It is in this province, which is styled the Greater India, at the gulf between Ceylon and the mainland, that the body of Messer St. Thomas lies, at a certain town having no great population.” Obviously this is a reference to the Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka, not the Mylapore beach area that is now called Santhome.” – Ishwar Sharan

USA Today Report

If Marco Polo spent years exploring China for the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan, as he claims, why do his reports contain no reference to the Great Wall, to Chinese tea-drinking ceremonies or to the practice of binding girls’ feet to keep them small?

In a new book, Did Marco Polo Go to China?, British librarian Frances Wood points out the holes in Polo’s account of his years in Asia and suggests he never made it to China.

“It is a terrific story; the only trouble is that there is no evidence to support it,” she says. “Like so many other great historical legends, the story is a myth.”

Other historians also have questioned whether Polo went to China, but none have succeeded in changing the prevailing view.

Since 1295, when the adventurous merchant returned, ragged and exhausted, to his home city of Venice after 24 years on the road, he has been accepted as the first European to travel right across Asia.

He told his story to a writer with whom he shared a jail cell in Genoa in 1299 after being taken prisoner in a sea battle. It became the travel epic, Divisament dou Monde, (Description of the World), which was received with astonishment and disbelief.

The account was the primary source for the European image of the Asia until the late 19th century. It stimulated Western interest in Asian trade and had a deep impact on other early voyages of discovery.

Columbus is known to have owned a copy, and studied it closely before sailing off in 1492, thinking he was headed for Asia.

Polo says he set off for China in 1271 with his father and uncle, bearing a letter from the papal legate in Acre and a bottle of oil from the lamp that burns in Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulchre.

In 1275, they arrived in Kublai Khan’s summer palace in Shangdu. At the time, the Mongol leader’s empire spread from China to the Mediterranean.

Polo says Kublai Khan took a liking to him because of his lively conversation, and sent him on fact-finding tours of his newly conquered territory.

In her book, published in October, Wood says that although Chinese sources of the period are littered with references to foreigners at the court of Kublai Khan, there is no mention of Marco Polo – or any Italians, for that matter.

And, although his report includes long descriptions of Chinese cities and aspects of life there, he “fails to remark upon the cultivation of the Yangtse delta area” and ignores the Great Wall and the practice of feet-binding.

Wood, who heads the Chinese section of the British Library, concedes that in Mongol times the Great Wall may not have had an uninterrupted run, and therefore may not have seemed so phenomenal. And as a city dweller, she adds, Polo may not have been attuned to agricultural developments.

His defenders argue that women with bound feet would have been closeted at home, invisible to a foreign visitor. But, says Wood, Odoric of Pordenone, a missionary who visited China 20 years later, described them in detail.

Wood admits that, “if Marco Polo was not in China, there is, unfortunately, nothing to prove he was anywhere else.”

Nevertheless, she concludes “that Marco Polo himself probably never traveled much further than the family’s trading posts on the Black Sea and in Constantinople,” pointing out that travelers who have tried to trace his footsteps have become lost at this point.

Wood argues that Marco Polo may have copied details from Persian or Arabic guidebooks on China that the Polo family collected on their travels.

That may explain why his vocabulary and some of his descriptions – notably of large fowl in southern China – tally with those of Persian and Arabic writers in some places, she said. – USA Today, London, 2 December 1999

Deccan Chronicle Report

Thirteenth century Venetian explorer Marco Polo never reached China, but lied about his trip to the Middle Kingdom after collecting second-hand information from Persian travellers he met on the shore of the Black Sea, according to a team of Italian archaeologists.

Knowledge of Marco Polo’s famed trip are based on The Travels of Marco Polo, as recounted to and written by a writer from Pisa named Rustichello.

The book has is often referred to as Il Milione, or “The Million” by sceptics of his million stories. Among the sceptics are the archaeologists from the University of Naples whose doubts were raised by historical errors pertaining to Marco Polo’s description of Kublai Khan’s attempted invasion of Japan in 1274 and 1281, said University of Naples archaeologist Daniele Petrella, interviewed in the current new edition of monthly history magazine Focus Storia. Mr. Petrella, director of an Italian archaeological dig in Japan, said he and other archaeologists were unable to find any “material proof, of concrete proof of his trip. In fact, it was this trip that made me doubt the tales.” Rather than reach Peking, the explorer may have reached the Black Sea where he listened to stories from Persian travellers who had been to China, Mr. Petrella said. – Deccan Chronicle, Chennai, August 5, 2011

The Myth of Saint Thomas and the Mylapore Shiva Temple Extract

“It is in this province, which is styled the Greater India, at the gulf between Ceylon and the mainland, that the body of Messer St. Thomas lies, at a certain town having no great population.” – Marco Polo in Il Milione (ca. 14th century)

Marco Polo, the famous Venetian traveller, is said to have visited South India twice, in 1288 and 1292, where he saw a tomb of St. Thomas “at a certain town” which he does not name. Many historians accept these dates and visits without question, and identify the little town that he speaks of with Mylapore. Yet it would appear that they are mistaken about the visits, as, indeed, was Marco Polo about the tomb of St. Thomas.[23]

Marco Polo left Acre, in Palestine, about 1272, carrying an introduction to the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, from his friend Pope Gregory X. He travelled with his father and uncle, by land, following the Silk Road north and east to China, which he reached about three years later. He remained in China for the next seventeen years, and was said to be at Yang-chou, in Kansu, around 1287. It is thus not possible for him to have been in South India in 1288 and this date can be rejected.

Macro Polo left China about 1292 with a fleet of fourteen ships, six hundred courtiers and sailors, and a princess whom he was to deliver to a khan in Persia. He sailed to Sumatra where he passed the monsoon, passed by the Nicobar Islands, passed through the Palk Strait into the Gulf of Mannar, stopped in Ceylon where he first heard the story of St. Thomas, then proceeded up the west coast of India and along the south coast of Persia until he reached Hormuz. From there he travelled by land to Khorasan with the princess, and then returned back down the Silk Road to Constantinople and Europe.

Macro Polo thus did not visit the Coromandel Coast in 1292 either, though this date still attracts many historians. Fosco Maraini, the Macro Polo authority at the University of Florence, in his Encyclopaedia Britannica article, is very positive about Marco Polo’s route and it did not include Mylapore.

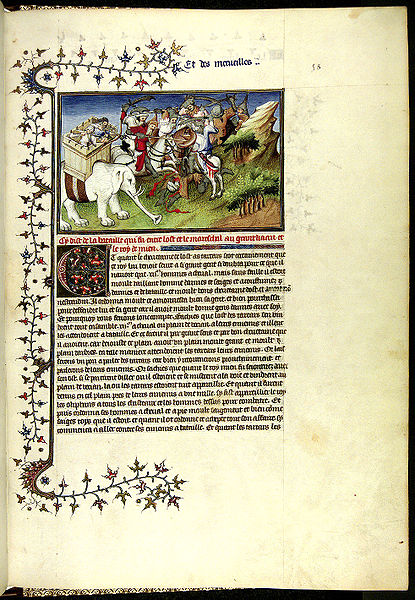

We would like to leave Marco Polo here but unfortunately he wrote a book, or, rather, in 1298 and 1299 dictated it to a fellow prisoner in Genoa―Venice and Genoa were always quarrelling and Marco had been captured by Genoa―one Rustichello, a writer of chivalrous romances and popular fiction. The book is called by different names in different languages. Originally, in the Old French in which it was written, it is called Livre des Merveilles du Monde (Book of the Marvels of the World), and in the Italian in which it was widely read, it is called Il Milione (The Million), a name which has the implied meaning of a tall tale. Dante Alighieri, author of The Divine Comedy and Marco Polo’s contemporary, seems to have regarded the book as a dangerous and impious invention. But it was an instant success in Venice and within a year was being read throughout southern Europe.

In the book Marco says the following about St. Thomas’s tomb: “It is in this province, which is styled the Greater India, at the gulf between Ceylon and the mainland, that the body of Messer St. Thomas lies, at a certain town having no great population.”

So the “certain town” of St. Thomas fame in Il Milione is on the Gulf of Mannar coast facing Ceylon, not the Mylapore seashore!

Macro Polo is the first writer in history to locate the tomb of St. Thomas on the sea and by doing so he revolutionizes the legend. All documents in the world prior to his locate the tomb on a mountain following the Acts of Thomas. Macro Polo is also the first writer in history to locate the tomb in South India, though some Christian scholars argue that Metropolitan Mar Solomon of Basra, in his Book of the Bee, ca. 1222, did this before him. They identify Mar Solomon’s Mahluph with Mylapore, but do this after the fact of the Portuguese identification of Mylapore with St. Thomas. There is no existing original manuscript of the Book of the Bee―as there is none of Il Milione―and various copies of it give various places of burial. One says “Mahluph” which has never been identified, a second “India” but not which India or where in which India, a third “Edessa”, and a fourth “Calamina”. Mar Solomon’s contemporary neighbour Bishop Bar-Hebraeus of Tigris, in his Matthaeus and Syriac-language Chronicle, ca. 1250, is more consistent. Like Mar Solomon, he says that St. Thomas preached to the Parthians, Medes and Indians (some add Hyrcanians and Bactrians), but in his books he asserts that the apostle was killed and buried at Calamina.[24]

Macro Polo collected his stories of St. Thomas from the Muslims and Syrian Christians―who were known to Europeans as Nestorians―in the ports of Ceylon and Malabar. However, Leonardo Olschki, in Marco Polo’s Asia, accepts Marco Polo’s claim that he had visited a Christian shrine on the Coromandel Coast, and also the opinion that the identity of the town that contained the shrine was Mylapore, but he does not accept that the shrine was the tomb of St. Thomas. In his commentary on Il Milione, he writes, “The shrine [of St. Thomas] is portrayed as isolated in a small village remote from everything, but the goal of continual pilgrimages consecrated by ancient and recent miracles. From Marco’s references we understand that it was then one of the characteristic Asiatic sanctuaries which, like the supposed tomb of the Magi in Persia, the Manichaean temple at Foochow, Adam’s sepulcher in Ceylon, and others not mentioned in Il Milione, had from time immemorial served the purposes of the various successive cults there, which rose and fell in a fangled mass of traditions, legends, and reciprocal influences now well-nigh impossible to unravel or specify. They are reflected in Marco’s data and observations with regard to this dispersed Indo-African Christianity, of which almost nothing is known from other sources but which is still worthy of study.

“The authenticity of St. Thomas’s tomb at Mailapur is almost as doubtful as that of Adam’s in Ceylon. However, while the latter arouses Marco’s suspicions because, as he asserts, the Holy Scriptures place it elsewhere, his critical faculties are lulled by the evidence of the miracles that the apostle continued to work in favour of the Christians of that region. He therefore accepted the opinion of the Nestorians of India, who venerated St. Thomas as the patron of Asiatic Christianity, and was unmindful of those numerous fellow believers who, with more legitimate reasons, had set up a whole mythology about his legendary tomb at Edessa.

“The first to describe this celebrated Indo-Christian sanctuary and to spread its fame abroad with his book, Marco transformed a place of pilgrimage not very widely important into a centre of Christian piety and propaganda, almost a far eastern peer of Santiago de Compostela [in Spain] at the western limits of the European world, with the difference that the tomb of St. Thomas was guarded by Christians opposed to the Church of Rome. The monks who dwelt near by, according to Marco’s account, lived on coconut ‘which the land there freely produces’. These religious must have been fairly numerous if, thirty years later, [in 1322,] when the cult was already in its decline, Friar Odoric of Pordenone counted some fifteen buildings about the sanctuary. This had in the meantime become a Hindu temple filled with idols, lacking any visible trace of its ancient Christian cult.[25] Friar John of Monte Corvino, on the other hand, after having passed some thirteen months in that region almost contemporaneously with Marco’s visit, says nothing of the apostle’s tomb, and mentions the church only in passing.”[26]

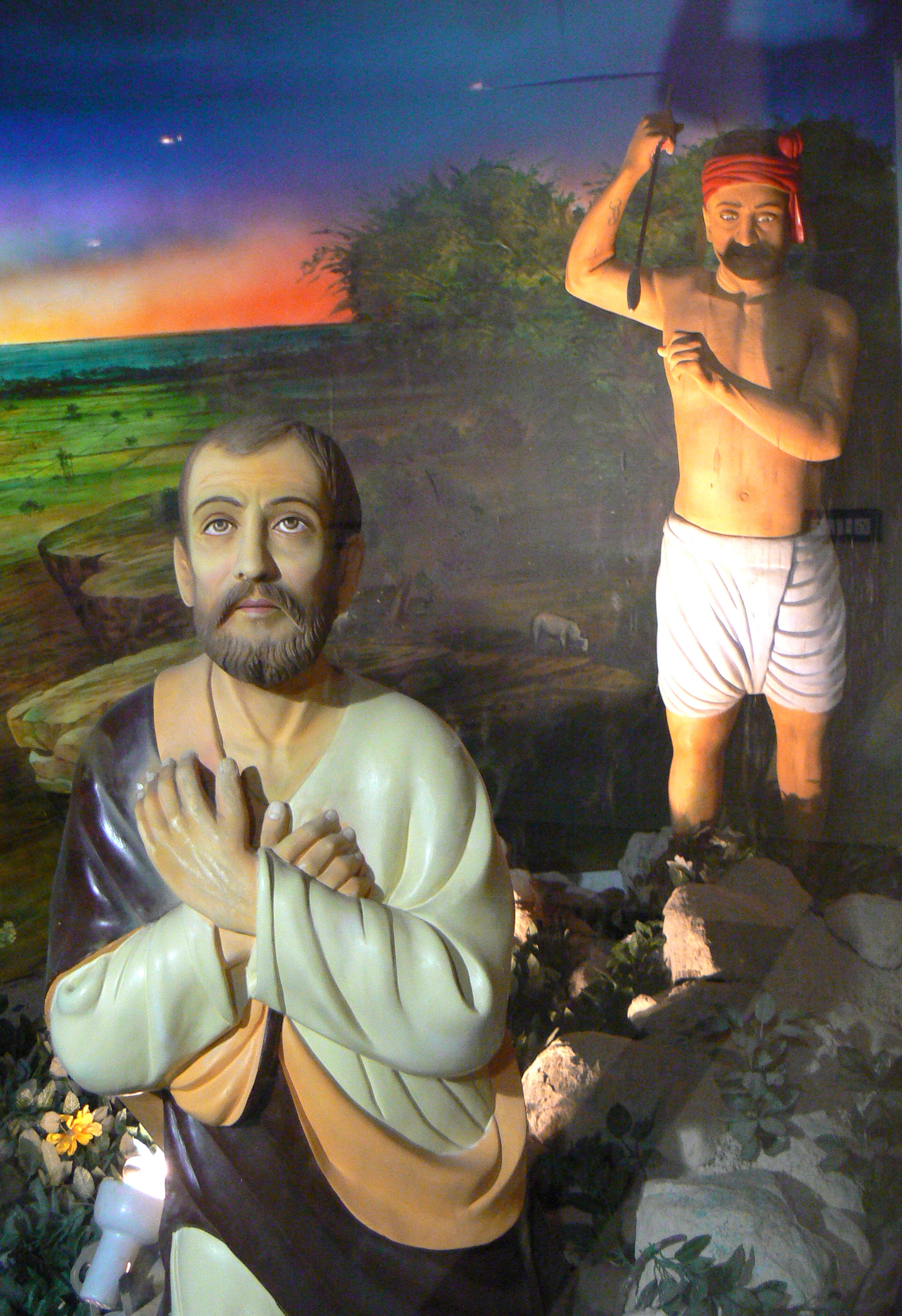

“The story of the apostle’s martyrdom told to Marco by the people of the country is far from original, and is probably of local origin. … We read in Il Milione that St. Thomas ended his days as the victim of a hunting accident when the arrow of a native pagan, aimed at a peacock, pierced the apostle’s right side while he was absorbed in prayer.”[27]

“No less worthy is the reference to Thomas’s apostolate in Nubia, which, according to information gathered by Marco at this sanctuary, was supposed to have preceded the saint’s sojourn in Coromandel; this would make Thomas the apostle of India and Africa, contrary to the legend that represents him as the evangelist of China.”[28]

Among the other stories told to Marco Polo by the Syrian Christians, is one that is very revealing. “We also learn from him,” writes Olschki, “of the first attempt known to us to suppress this cult, which was carried out … by the sovereign of that kingdom. Indeed, when a pagan ruler of the region filled with rice the church and monasteries of Mailapur, in order to put an end to the Christian practices of the Nestorian rites, the apostle threateningly appeared to him in a dream and made him so far change his ways as to exempt the faithful from all tribute and to safeguard the church from violation.”

Olschki calls this a conventional piece of hagiography, but there is more in it then the pious account of a saint exercising his occult power over a persecuting ruler.

The Hindu king did not of course violate a church―in all of Indian history there is no evidence of such acts; Hindu kings gave generous donations for the building of churches and had already done so in Malabar―nor would he have objected to the rites that were being performed in a Christian church. The king would have objected to Christian rites being performed in a Hindu temple, and would have certainly put a stop to them. He would have had the temple filled with raw rice as part of a suddhi (purification) or pratistha (consecration) ritual; or, again, he would have been doing anna abhisheka (food offering) to the Lord by filling the sanctum with huge quantities of cooked rice―even as it is done today in the great Shiva temples of South India.

What emerges from this story is that the Syrian Christians were worshipping in a Hindu temple, which they called a church, at least up to 1322 when Friar Oderic visited Mylapore. Henry Yule, in Cathay and the Way Thither, referring to Friar Oderic’s description of the church, declares, “This is clearly a Hindu temple.”[29]

Marco Polo did not visit Mylapore; indeed, Mylapore is not identified in Il Milione though it may be inferred to be the destination of Christian pilgrims from later Portuguese tales. Marco Polo is only repeating the pious stories of Christians and Muslims―the latter also claimed St. Thomas; he was, they told Marco, not only an apostle from Nubia, but a Muslim apostle[30]―who apparently worshipped in a Hindu temple, each justifying his presence there by identifying the shrine with his own Thomas.[31] – Ishwar Sharan, Chapter 7, Pages 81-88, 2019

23. Some historians theorise that Marco Polo never left Constantinople to travel to China, but collected all his adventure stories from Muslim and Syrian Christian merchants who came to the great city to trade. They argue that he compiled these travel tales into a book and claimed them as his own experiences. Certainly in his own time he was not believed and Dante Alighieri called him a liar. In this book we assume the traditional story of his travels to be partly true.

24. Hippolytus, the third century Roman theologian and antipope, is the earliest writer to say that St. Thomas was martyred and buried at Calamina, which he claims is in India. He is followed at the end of the third century by Dorotheus of Tyre, and in the seventh century by Sophronius of Jerusalem and Isidore of Seville. Thomas Herbert identifies Calamina with Gouvea in Brazil, T.K. Joseph with Kalawan near Taxila, P.V. Mathew with Bahrain, and Veda Prakash with Kalamai in Greece. Calamina has never been identified and ancient Thebes northwest of Athens may be added to the list of conjectures. It was originally known as Cadmeia and often called that up to the end of the second century CE. Cadmeia when Latinized becomes Calamina. The earth from the single grave of its twin heroes, Amphion and Zethus, was believed to contain great power and was protected, even as the earth of St. Thomas’s sepulchre was believed to heal. Cadmean or Thebean earth, called calamine, is pink in colour and used in medicine and metallurgy.

25. The earliest records of the Madras area, including money-lenders’ accounts, go back to the fourth century CE. They identify Mylapore, Triplicane and Tiruvottiyur as temple towns. The Nandikkalambakkam describes Mylapore as a prosperous port under the Pallavas, the early-fourth-to-late-ninth century emperors of Kanchipuram, who patronized various schools of Hinduism including Jainism and Buddhism, built temples and generously supported the arts. There is no record of a Christian church or saint’s tomb at Mylapore before the Portuguese period, and Olschki is basing his comments on the wrong assumption that Marco Polo did visit Mylapore and that he found a church there. Friar Oderic is describing the original Kapaleeswara Shiva Temple on the Mylapore seashore, which the Tamil saint Jnanasambandar has positively identified as being there at least before the sixth century CE.

26. Friar John, in his letters from China (presumably sent to Rome), does not identify the St. Thomas church that he visited or say where it was located. Most scholars believe that he travelled in Malabar and the Konkan only.

27. Olschki’s note: “Thus, St. Thomas was supposed to have been a victim but not a martyr―which would add further complications to the already tangled mass of fables concerning his apostolate and his end.”

28. Olschki’s note: “The oriental ubiquity of St. Thomas’s apostolate is explained by the fact that the geographical term ‘India’ included, apart from the subcontinent of this name, the lands washed by the Indian Ocean as far as the China Sea in the east and the Arabian peninsula, Ethiopia, and the African coast in the west.”

29. Friar Oderic is not the only mediaeval European traveller to mistake a temple for a church. Vasco da Gama did the same in 1498. He believed the temples he visited in Calicut were churches and the images he prayed before were those of Christian saints. His error was corrected on his second visit, when the Syrian Christians identified themselves and invited him to overthrow the Zamorin and take over the kingdom.

30. See T.K. Joseph’s Six St. Thomases of South India: A Muslim Non-Martyr (Thawwama) made Martyrs after 1517 AD.

31. The Syriac “Thoma” and “Thama” and Arabic “Thuma” and “Thawwama” are variations of the name Thomas. They all have the same meaning―”born twin”―and were common names in the Christian and Muslim communities of India and West Asia.