It cannot be overlooked that the Catholic Church hails an arch criminal like Francis Xavier as the Patron Saint of the East. His carcass (or plaster cast) is still worshipped as a holy relic and the basilica where it is enshrined remains a place of Christian pilgrimage. – Sita Ram Goel

Francis Xavier: Inviter of the Inquisition to India

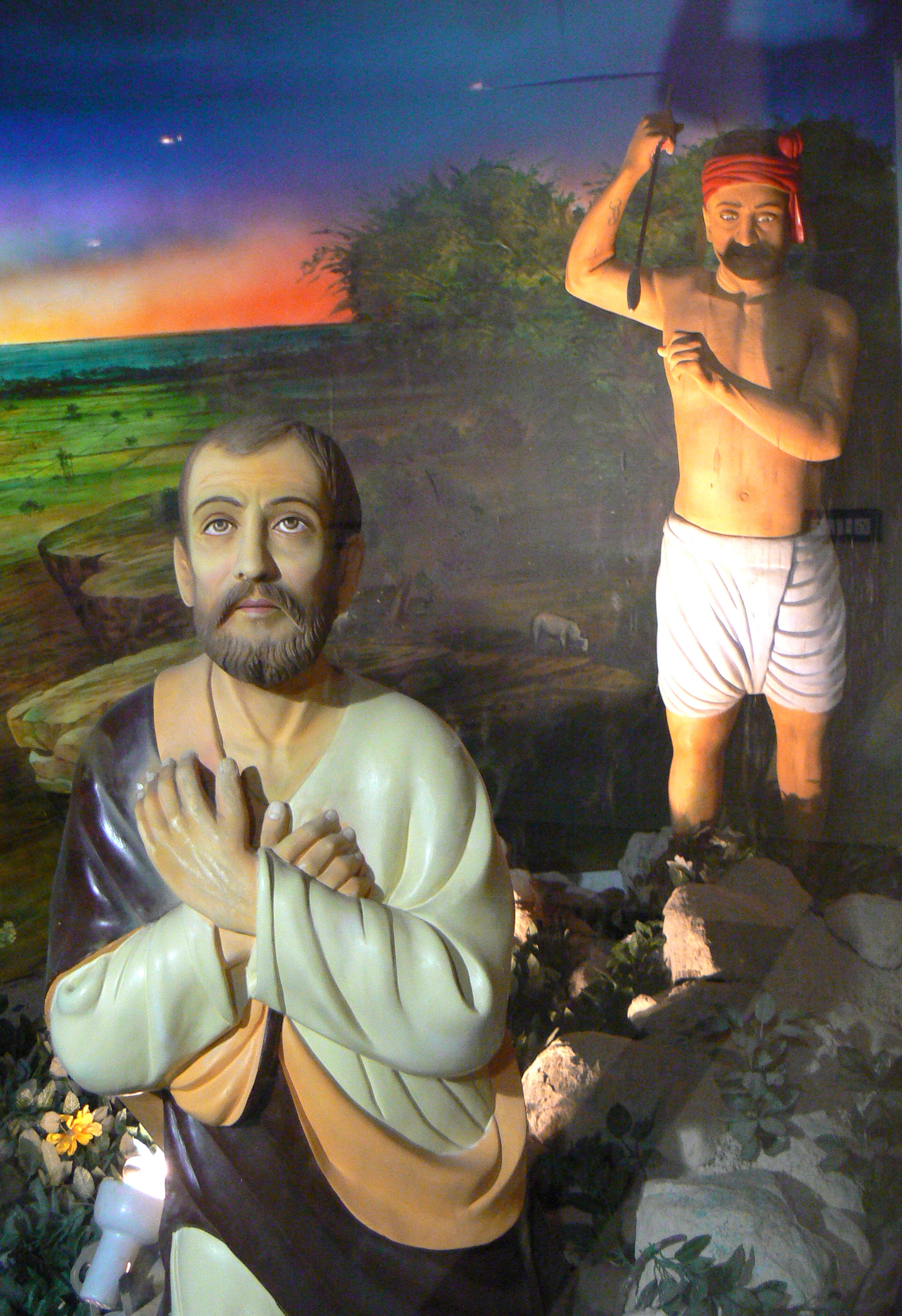

The next encounter between Hinduism and Christianity commenced with the coming of Christian missionaries to Malabar after Vasco da Gama found his way to Calicut in AD 1498. It took a serious turn in AD 1542 when Francis Xavier, a rapacious pirate dressed up as a priest, arrived on the scene. The proceedings have been preserved by the Christian participants. They make the most painful reading in the history of Christianity in India. Francis Xavier had come with the firm resolve of “uprooting paganism” from the soil of India and planting Christianity in its place. His sayings and doings have been documented in his numerous biographies and cited by every historian of the Portuguese episode in the history of India.

Francis Xavier was convinced that Hindus could not be credited with the intelligence to know what was good for them. They were completely under the spell of the Brahmanas who, in turn, were in league with evil spirits. The first priority in India, therefore, was to free the poor Hindus from the stranglehold of the Brahmanas and destroy the places where evil spirits were worshipped. A bounty for the Church was bound to follow in the form of mass conversions.[1]

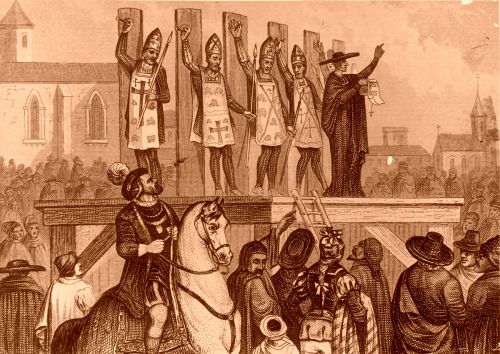

We shall let a Christian historian [of the Goa Inquisition] speak about what the Portuguese did in their Indian domain. “At least from 1540 onwards,” writes Dr. T. R. de Souza, “and in the island of Goa before that year, all the Hindu idols had been annihilated or had disappeared, all the temples had been destroyed and their sites and building materials were in most cases utilised to erect new Christian churches and chapels. Various viceregal and Church council decrees banished the Hindu priests from the Portuguese territories; the public practice of Hindu rites including marriage rites, was banned; the state took upon itself the task of bringing up the Hindu orphan children; the Hindus were denied certain employments, while the Christians were preferred; it was ensured that the Hindus would not harass those who became Christians, and on the contrary, the Hindus were obliged to assemble periodically in churches to listen to preaching or to the refutation of their religion.”[2]

Coming to the performance of the missionaries, he continues: “A particularly grave abuse was practised in Goa in the form of ‘mass baptism’ and what went before it. The practice was begun by the Jesuits and was later initiated by the Franciscans also. The Jesuits staged an annual mass baptism on the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul (25 January), and in order to secure as many neophytes as possible, a few days before the ceremony the Jesuits would go through the streets of the Hindu quarters in pairs, accompanied by their Negro slaves, whom they would urge to seize the Hindus. When the blacks caught up a fugitive, they would smear his lips with a piece of beef, making him an ‘untouchable’ among his people. Conversion to Christianity was then his only option.”[3]

Finally, he comes to “Financing Church Growth” and concludes: “… the government transferred to the Church and religious orders the properties and other sources of revenue that had belonged to the Hindu temples that had been demolished or to the temple servants who had been converted or banished. Entire villages were taken over at times for being considered rebellious and handed over with all their revenues to the Jesuits. In the villages that had submitted themselves, at times en masse, to being converted, the religious orders promoted competition to build bigger and bigger churches and more chapels than their neighbouring villages. Such a competition, drawing funds and diverting labour, from other important welfare works of the village, was decisively bringing the village economy in Goa into bankruptcy.”[4]

During the same period, Christianity was spreading its tentacles to Bengal. Its patrons were the same as in Goa; so also its means and methods. “The conversion of the Bengalis into Christianity,” writes Dr. Sisir Kumar Das, “not only coincided with the activities of the Portuguese pirates in Bengal but the pirates took an active interest in it.”[5] The Augustinians and Jesuits manned the mission with bases at Chittagong in East Bengal and Bandel and Hooghly in West Bengal. Mission stations were established at many places in the interior. “It was the boast of the Hooghly Portuguese,” records Dr. P. Thomas, “that they made more Christians in a year by forcible conversions, of course, than all the missionaries in the East in ten.”[6]

The Portuguese captured the young prince of Bhushna, an estate in Dhaka District. He was converted by an Augustinian friar, Father D’Rozario and named Dom Antonio de Rozario. The prince, in turn, converted 20,000 Hindus in and around his estate. “The Jesuits came forward,” continues Dr. Das, “to help the neophytes to minister to the needs of the converts and this created bitterness between Augustinians and Jesuits…. In 1677, the Provincial at Goa deputed Father Anthony Magalheans, the Rector of the College at Agra, to visit and report on this problem. According to his report nearly 25,000, if not more, converts were there but they had hardly any knowledge of Christianity…. He also observed that many of them became Christians to get money. The Marsden Manuscripts now preserved in the British Museum containing letters of Jesuit Fathers, give evidence that Portuguese missionaries gave money to perspective converts to allure them.”[7]

The quality of the converts, though bewailed frequently by the missionaries, did not really perturb them. Frey Duarte Nunes, the prelate of Goa, had foreseen the situation as early as 1522. According to him, “even if the first generation of converts was attracted by rice or by any other way and could hardly be expected to become good Christians, yet their children would become so with intensive indoctrination, and each successive generation would be more firmly rooted.”[8]

It was a very difficult situation for Hinduism. But, by and large, Hindus chose to stay in the faith of their forefathers in spite of all trials and temptations. There was no mass movement towards the Church except the “mass baptisms” staged by the Jesuits. The mission was in a fix. The strategy of forced conversions recommended by Francis Xavier had failed.

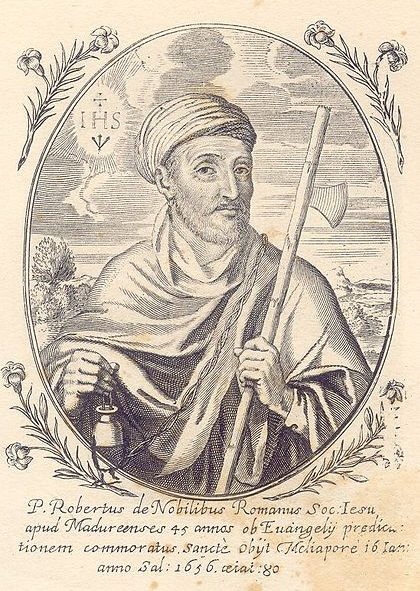

Roberto de Nobili: The impostor from Rome

Another Jesuit, Robert De Nobili, came forward with a new strategy. When he came to the Madurai Mission in 1606, he had found it a “desert” in terms of conversions. He had also seen that Hindus had retained their reverence for the Brahmanas in spite of missionary insinuations. So he decided that he would disguise himself as a Brahmana and preach the gospel by other means. The story is well known—how he put on an ochre robe, wore the sacred thread, grew a tuft of hair on his head, took to vegetarian food, etc., in order to pass as a Brahmana. He also composed some books in Tamil and Sanskrit, particularly the one which he palmed off as the Yajurveda. When some Hindus suspected from the colour of his skin that he was a Christian, he lied with a straight face that he was a high-born Brahmana from Rome!

Some Christian historians credit De Nobili with converting a hundred thousand Hindus. Others put the figure at a few hundred. But all agree that his converts melted away very fast soon after he was exposed by other missionaries who were either jealous of him or did not like his methods. Christian theologians hail him as the pioneer of indigenisation (inculturation) in India and the founder of the first Christian ashram. A truly ethical criterion would dismiss him as a desperate and despicable scoundrel.[9]

One wonders how Hinduism would have fared in South India if its encounter with Christianity under the Portuguese dispensation had continued uninterrupted. Hindus were helpless wherever Portuguese power prevailed and Hindus outside could not help as they themselves were groaning under the heel of Islamic imperialism after the defeat of the Vijayanagara Empire by a Muslim alliance in 1565 AD. The situation was saved by the Dutch in the second quarter of the seventeenth century. The Dutch destroyed the maritime monopoly of the Portuguese and drove them out of Malabar and southern Tamil Nadu. Christianity had to break its encounter with Hinduism except in the small Portuguese enclaves where it continued for two more centuries. But most of the heat applied on Hinduism had to be taken off because “the fear of retaliatory raids by the powerful Marathas in the neighbourhood acted as an effective check on the missionary zeal and coercion.”[10]

A plausible case has been made by Christian historians, namely, that the Portuguese were using Christianity as a cover for their predatory imperialism. But what about the Augustinians and the Dominicans and the Franciscans, all of whom belonged to the holy orders? And what about Francis Xavier and his Jesuits? It cannot be overlooked that the Catholic Church hails an arch criminal like Francis Xavier as the Patron Saint of the East. His carcass (or plaster cast) is still worshipped as a holy relic and the basilica where it is enshrined remains a place of Christian pilgrimage. It is shameless dishonesty to say that the Christian doctrine had nothing to do with the atrocities practised in Goa and Bengal and elsewhere under the Portuguese dispensation.[11]

› Excerpted from Sita Ram Goel’s History of Hindu-Christian Encounters, Voice of India, New Delhi, 1996.

1. Francis Xavier was the pioneer of anti-Brahmanism which was adopted in due course as a major plank in the missionary propaganda by all Christian denominations. Lord Minto, Governor General of India from 1807 to 1812, submitted a Note to his superiors in London when the British Parliament was debating whether missionaries should be permitted in East India Company’s domain under the Charter of 1813. He enclosed with his Note some “propaganda material used by the missionaries” and, referring to one missionary tract in particular, wrote: “The remainder of this tract seems to aim principally at a general massacre of the Brahmanas” (M. D. David (ed.), Western Colonialism in Asia and Christianity, Bombay, 1988, p. 85). Anti-Brahmanism has become the dominant theme in the speeches and writings of Indian secularists of all sorts.

2. M.D. David (ed.), op.cit., p. 17.

3. Ibid., p. 19.

4. Ibid., pp. 24-35. For a detailed account of Christian doings in Goa, see A.K. Priolkar, The Goa Inquisition, Bombay, 1961, Voice of India reprint, New Delhi, 1991 and 1996.

5. Sisir Kumar Das, The Shadow of the Cross, New Delhi, 1974, p. 4.

6. P. Thomas, Christians and Christianity in India and Pakistan, London, 1954, p. 114.

7. Sisir Kumar Das, op. cit., p. 5.

8. M.D. David (ed.), op. cit., p. 8.

9. The masquerade of Robert Di Nobili has been described in detail in Sita Ram Goel, Catholic Ashrams: Sannyasins or Swindlers?, Voice of India, New Delhi, 1995.

10. M.D. David (ed.) op. cit., p. 19.

11. Francis Xavier was the official Apostle of India up to 1953. He was replaced by Judas Thomas Didymus — St. Thomas — after this date because his crimes had become known to the Indian public and he had become an embarrassment to the Jesuits and Catholic Church in India. The Church regarded Thomas the better choice because according to the fable he had died a martyr in India at the hands of a Hindu king or priest. Christianity is a martyrolatrous religion and cannot tolerate saints and apostles who die natural deaths. The St. Thomas fable was much more useful to the politically ambitious and communally-minded Indian Church as it gave her a stick to beat Hindus with. – IS

“Goa is sadly famous for its Inquisition, equally contrary to humanity and commerce. The Portuguese monks made us believe that the people worshipped the devil, and it is they who have served him.” – Voltaire

Xavier’s resting place replaces Shiva temple

The Church of Bom Jesus displaced a Saptakotishwar Shiva Temple in Old Goa. This was a second temple as the main deity was at Narve.

Saptakotishwar was the deity of the Kadamba dynasty around the twelfth century. The main temple was at Narve. It was destroyed by the Bahamani Sultan Allauddin Hasan Gangu in 1352, and rebuilt in 1367 by Vijayanagar King Harihararaya.

Because the church replaces a Shiva temple, there is a tradition in Goa that the Basilica of Bom Jesus—a basilica is a church that has special privileges, i.e. the bishop has a private altar to say Mass and doesn’t have to share altars with the parish priest—cannot keep a cross on the roof of the church. It keeps falling down for one reason or another.

A rejoinder to Paulo Coelho’s paean to Francis Xavier – Ishwar Sharan

In a propaganda coup that would leave a Jesuit missionary strategist breathless, popular author Paulo Coelho has written a romanticized eulogy of the notorious 16th century Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier. Coelho is a born-again Catholic who has received a no objection certificate from the Pope and is a candidate for Opus Dei.

Paulo Coelho does not think Indians know their own history or that of the Spanish missionary. He tells us as much in an article called “Francisco of Xavier” published in the Chennai edition of the Deccan Chronicle on 3 November 2006. The Deccan Chronicle accommodates him without thought or concern for the intelligence or feelings of its mostly Hindu readers. Many of these readers are deeply offended by Coelho’s praise of a psychopath who today would be put on trial for fomenting religious hatred and crimes against humanity.

The truth, documented, that Francis Xavier was a religious bigot and temple-breaker who believed in forced conversion and invited the Inquisition to Goa to further this evil practice, is not a truth these editors want to know. They prefer Paulo Coelho’s truth, seemingly innocuous but very misleading. In his paean to Francis Xavier, Coelho writes:

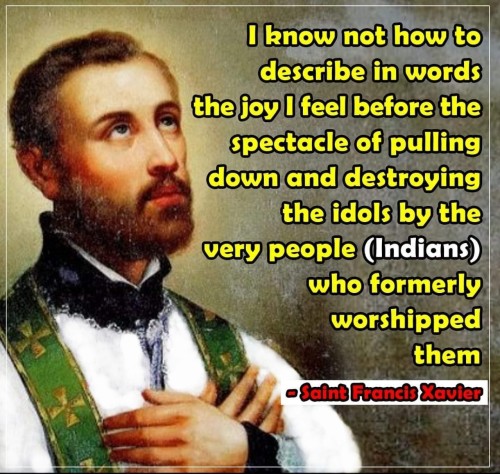

The “encouragement and hope” that Francis Xavier brought to the “less privileged” people of India, and the “light and heat” that he shed on them, is best described in his own words in a letter he sent to Jesuit headquarters in Rome:

Xavier did this after the Hindu Raja of Quilon had given him a large grant to build churches. In another letter he writes:

Francis Xavier was the pioneer of anti-Brahmin rhetoric in India. It would be adopted as a major propaganda tool by all Christian denominations operating missions in India, and it became a dominant theme in the speeches and writings of Indian secularists after Independence. A Muslim or Christian defending his faith is a hero or a martyr recognised in the world, but a Hindu doing the same in his own village is reviled as a “wicked and crafty man born of a unholy race”. Such is the perversion of Christian and secularist dialectic in the 16th century and today.[1]

Xavier’s violent career in India destroyed families and ancient cultured communities, and alienated the new converts from their society and Gods. It left them without love for their neighbours or a universal ethic to live by. It destroyed their faith. In Christian doctrine, to attack a man’s faith is a sin against the Holy Spirit. It is a sin that cannot be forgiven. It is the sin Francis Xavier is guilty of. But Xavier was a Christian missionary and his victims were heathens not human beings, and instead of being condemned he was canonized and made a saint. Such is the perversion of Christian reason and the evil deeds that follow from this reasoning.

Francis Xavier begged his superiors in Rome and Portugal to send the Inquisition to India so that he could continue his mission of forced conversions. He died before the Inquisition could arrive. He could not have the pleasure or satisfaction of watching obstinate Hindus and backsliding converts, their breasts and genitals cut off, burn at the stake in Old Goa. But he did gain a posthumous victory over the hated Brahmin. His bones lie in a silver casket in the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Old Goa, the church built on the site of an ancient Shiva temple destroyed by the Portuguese.

About the ‘secular’ Deccan Chronicle newspaper

The Deccan Chronicle is a popular anti-Brahmin,[2] pro-Catholic newspaper and the newest proponent of the St. Thomas fable as Indian history (following The Hindu and The New Indian Express). It hides its pro-St. Thomas agenda behind a correspondent’s by-line and the provocative statement of the Santhome Cathedral parish priest: “The existence of the Santhome Church is a proof by itself that Christianity in India is more than 2000 years old” (DC, Chennai, 8 April 2007).

For sucking up to the Catholic clergy, the Deccan Chronicle is the leader among Indian newspapers. Its editors (this article was written in 2006), M.J. Akbar and Naazreen Bhura, both self-righteous secularists of the Nehruvian school, assiduously follow the Christian practice of treating Christian legend as history and Hindu history as mythology (or put another way, treating Christian superstition as tradition and Hindu tradition as superstition). In true Indian secularist fashion, they do not tolerate dissent, and letters to the editor concerning Paulo Coelho’s eulogy of the criminal Xavier or Sivarajan’s treatment of the St. Thomas legend as Indian history, are not published. For Akbar and Bhura, criticism of themselves or their “eminent” contributors is a manifestation of Hindu communalism. Indeed, dissent can attract a spiteful response from the editor memsahib, Naazreen Bhura. For both editors, whose decisions influence the opinions of half a million readers every day, facts and figures are extraneous irritants to be ignored, except where the facts and figures can be employed in subtle Hindu-bashing exercises[3], or otherwise to whitewash the bigoted and violent history of Christianity in India. At the same time, Akbar pontificates loudly and at great length about ethical journalism and telling the truth in print however unsavoury the truth may be. To prove his point, he has presented Sunday morning readers with the unsavoury truth of his mutilated penis in a personalised editorial. He is an exhibitionist, a celebrity journalist and jihadi apologist (see his Shade of Swords), and a very clever falsifier of Islamic history who can get away with murder in print.

And get away with the murder of print: he was one of the first Indian journalists to call for a ban on Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, an act which aligned him with Muslim fundamentalists and provoked shocked European intellectuals to call him, ironically, “a true green Nehruvian secularist”.[4] — Ishwar Sharan

Notes

1. There is a story that the first debate Francis Xavier had with Brahmins took place in the Tiruchendur Murugan Temple on the south coast of Tamil Nadu. He preached and they listened carefully. Then they laughed. They told him that his conception of God was immature and inadequate. God was beyond number and count, neither one nor three-in-one as he claimed. His idea that God had only one incarnation in history was absurd and served a selfish purpose, denying God to other nations and peoples. It placed unacceptable limitations on an all-powerful, all-pervasive, all-compassionate God. Xavier left the temple courtyard in disgrace, to proselytize the helpless fishermen, and Brahmins became his feared, implacable enemy.

2. Anti-Brahminism and anti-Semitism are the same ethno-religious prejudice directed at an accomplished minority group who are perceived, wrongly, to be the cause of a nation’s social and economic ills, or, otherwise, to be controlling a nation’s cultural, political, or economic destiny from behind the scenes in their own interest. Koenraad Elst, in Indigenous Indians: Agastya to Ambedkar, writes, “In fact, apart from anti-Judaism, the anti-Brahmin campaign started by [Christian] missionaries is the biggest vilification campaign in world history.”

3. An example of an anti-Hindu exercise is the use of the term “idol” for Hindu images. Technically correct, the word is loaded with negative connotations and is part of the abusive rhetoric of Christian evangelists. The same newspaper on another page uses the neutral term “statues” for Christian images. Clearly, there is editorial bias at work here. In the forty years that I have lived in India, I have never met a Hindu who worships idols. Hindus worship God, and even a simple village woman knows that God is spirit not matter.

4. Article quoted “Francisco of Xavier” by Paulo Coelho, English translation (C) James Mulholland, published in the Deccan Chronicle, Chennai edition, 3 November 2006. Article quoted in part only.

› See the latest Ignatius and Xavier eulogy in the Deccan Chronicle by Jesuit Fr. Francis Gonsalves called “For God’s greater glory“. Gonsalves can be contacted at fragons@gmail.com

› Paulo Coelho can be contacted at https://paulocoelhoblog.com/