“If we want to ensure that our youth remain committed to Hinduism as a meaningful path, that our leaders teach Hinduism in a manner that represents the tradition faithfully and with dignity, and that the greater Hindu community can feel that they have a religion that they can truly take pride in, then we must abandon Hindu Universalism. … Let us teach them Sanatana Dharma, the eternal way of Truth.” – Dr. Frank Morales

It is by no means an exaggeration to say that the ancient religion of Hinduism has been one of the least understood traditions in the history of world religion. The sheer number of stereotypes, misconceptions and outright false notions about what Hinduism teaches, as well as about the precise practices and behavior that it asks of its followers, outnumber those of any other religion currently known. Leaving the more obviously grotesque crypto-colonialist caricatures of cow worship, caste domination and sati aside, even many of the most fundamental theological and philosophical foundations of Hinduism often remain inexplicable mysteries to the general public and supposed scholars of Hindu studies. More disturbing, however, is the fact that many wild misconceptions about the beliefs of Hinduism are prevalent even among the bulk of followers of Hinduism and, alarmingly, even to many purportedly learned spiritual teachers, gurus and swamis who claim to lead the religion in present times.

Of the many current peculiar concepts mistakenly ascribed to Hindu theology, one of the most widely misunderstood is the idea that Hinduism somehow teaches that all religions are equal, that all religions are the same, with the same purpose, goal, experientially tangible salvific state and object of ultimate devotion. So often has this notion been thoughtlessly repeated by so many–from the common Hindu parent to the latest swamiji arriving on American shores yearning for a popular following–that it has now become artificially transformed into a supposed foundation stone of modern Hindu teachings. Many Hindus are now completely convinced that this is actually what Hinduism teaches. Despite its widespread popular repetition, however, does Hinduism actually teach the idea that all religions are really the same? Even a cursory examination of the long history of Hindu philosophical thought, as well as an objective analysis of the ultimate logical implications of such a proposition, quickly makes it quite apparent that traditional Hinduism has never supported such an idea.

The doctrine of what I call “Radical Universalism” makes the claim that all religions are the same. This dogmatic assertion is of very recent origin, and has become one of the most harmful misconceptions in the Hindu world in the last 150 or so years. It is a doctrine that has directly led to a self-defeating philosophical relativism that has, in turn, weakened the stature and substance of Hinduism to its very core. The doctrine of Radical Universalism has made Hindu philosophy look infantile in the eyes of non-Hindus, has led to a collective state of self-revulsion, confusion and shame in the minds of too many Hindu youth, and has opened the Hindu community to be preyed upon much more easily by the zealous missionaries of other religions. The problem of Radical Universalism is arguably the most important issue facing the global Hindu community today.

What’s a kid to do?

Indian Hindu parents are to be given immense credit. The daily challenges they face in encouraging their children to maintain their commitment to Hinduism are enormous and well-known. Hindu parents try their best to observe fidelity to the religion of their ancestors, often having little understanding of the religion themselves, other than what was given to them, in turn, by their own parents. All too many Indian Hindu youth, on the other hand, find themselves unattracted to a religion that is little comprehended or respected by most of those around them–Hindu and non-Hindu alike. Today’s Hindu youth seek more strenuously convincing reasons for following a religion than merely the argument that it is the family tradition. Today’s Hindu youth demand, and deserve, cogent philosophical explanations about what Hinduism actually teaches, and why they should remain Hindu rather than join any of the many other religious alternatives they see around them. Temple priests are often ill-equipped to give these bright Hindu youth the answers they so sincerely seek; mom and dad are usually even less knowledgeable than the temple pujaris. What is a Hindu child to do?

As I travel the nation delivering lectures on Hindu philosophy and spirituality, I frequently encounter a repeated scenario. Hindu parents will approach me after I’ve finished my lecture and timidly ask for advice. The often-repeated story goes somewhat like this: “We raised our daughter (or son) to be a good Hindu. We took her to the temple for important holidays. We even sent her to a Hindu camp for a weekend when she was 13. Now at the age of 23, our child has left Hinduism and converted to the (fill in the blank) religion. When we ask how she could have left the religion of her family, the answer she throws back in our face is: ‘Mama/dada, you always taught me that all religions are the same, and that it doesn’t really matter how a person worships God. So what does it matter if I have followed your advice and switched to another religion?’ “

Many of you reading this article have probably been similarly approached by parents expressing this same dilemma. The truly sad thing about this scenario is that the child is, of course, quite correct in her assertion that she is only following the logical conclusion of her parents’ often-repeated mantra all religions are the same. If all religions are exactly the same, after all, and if we all just end up in the same place in the end anyway, then what does it really matter what religion we follow? Hindu parents complain when their children adopt other religions, but without understanding that it was precisely this flawed dogma of Radical Universalism, and not some inherent flaw of Hinduism itself, that has driven their children away. My contention is that parents themselves are not to be blamed for espousing this non-Hindu idea to their children. Rather, much of the blame is to be placed at the feet of today’s ill-equipped Hindu teachers and leaders, the guardians of authentic Dharma teachings.

In modern Hinduism, we hear from a variety of sources this claim that all religions are equal. Unfortunately, the most damaging source of this fallacy is none other than the many uninformed spiritual leaders of the Hindu community itself. I have been to innumerable pravachanas (expositions), for example, where a guruji will provide his audience with the following metaphor, which I call the Mountain Metaphor. “Truth (or God or Brahman) lies at the summit of a very high mountain. There are many diverse paths to reach the top of the mountain, and thus attain the one supreme goal. Some paths are shorter, some longer. The path itself, however, is unimportant. The only truly important thing is that seekers all reach the top of the mountain.”

While this simplistic metaphor might seem compelling at a cursory glance, it leaves out a very important elemental supposition: it makes the unfounded assumption that everyone wants to get to the top of the same mountain! As we will soon see, not every religion shares the same goal, the same conception of the Absolute (indeed, even the belief that there is an Absolute), or the same means to their respective goals. Rather, there are many different philosophical “mountains,” each with its own unique claim to be the supreme goal of all human spiritual striving.

A tradition of tolerance, not capitulation

Historically, pre-colonial, classical Hinduism never taught that all religions are the same. This is not to say, however, that Hinduism has not believed in tolerance or freedom of religious thought and expression. It has always been a religion that has taught tolerance of other valid religious traditions. However, the assertion that a) we should have tolerance for the beliefs of other religions is a radically different claim from the overreaching declaration that b) all religions are the same. This confusion between two thoroughly separate assertions may be one reason why so many modern Hindus believe that Hindu tolerance is synonymous with Radical Universalism. To maintain a healthy tolerance of another person’s religion does not mean that we have to then adopt that person’s religion!

Uniquely Hindu: The crisis of the Hindu lack of self-worth

In general, many of the world’s religions have been periodically guilty of fomenting rigid sectarianism and intolerance among their followers. We have witnessed, especially in the record of the more historically recent Western religions, that religion has sometimes been used as a destructive mechanism, misused to divide people, to conquer others in the name of one’s god, and to make artificial and oppressive distinctions between “believers” and “non-believers.” Being an inherently non-fundamentalist worldview, Hinduism has, by its nature, always been keen to distinguish its own tolerant approach to spirituality vis-à-vis more sectarian and conflict-oriented notions of religion. Modern Hindus are infamous for bending over backwards to show the world just how nonfanatical and open-minded we are, even to the point of denying ourselves the very right to unapologetically celebrate our own Hindu tradition.

Unfortunately, in our headlong rush to unburden Hinduism of anything that might seem to even remotely resemble the closed-minded sectarianism sometimes found in other religions, we often forget the obvious truth that Hinduism is itself a systematic and self-contained religious tradition in its own right. In the same manner that Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Taoism or Jainism have their own unique and specific beliefs, doctrines and claims to spiritual authority, all of which fall within the firmly demarcated theological bounds of their own unique traditions, Hinduism, too, has just such Hindu-centric theological and institutional bounds. Like every other religion, Hinduism is a distinct and unique tradition, with its own inbuilt beliefs, worldview, traditions, rituals, concept of the Absolute, metaphysics, ethics, aesthetics, cosmology, cosmogony and theology. The grand, systematic philosophical construct that we today call Hinduism is the result of the extraordinary efforts and spiritual insights of the great rishis, yogis, acharyas and gurus of our religion, guided by the transcendent light of the Vedic revelation that has stood the test of time. It is a tradition that is worthy of healthy celebration by Hindus and respectful admiration by non-Hindus.

Such a realization and acceptance of Hinduism’s unique place in the world does not, by any stretch of the imagination, have to lead automatically to sectarianism, strife, conflict or religious chauvinism. Indeed, such a recognition of Hinduism’s distinctiveness is crucial if Hindus are to possess even a modicum of healthy self-understanding, self-respect and pride in their own tradition. Self-respect and the ability to celebrate one’s unique spiritual tradition are basic psychological needs, and a cherished civil right of any human being, Hindu and non-Hindu alike.

Letting the tradition speak for itself

When we look at the philosophical, literary and historical sources of the pre-colonial Hindu tradition, we find that the notion of Radical Universalism is overwhelmingly absent. The idea that all religions are the same is not found in the sacred Hindu literature, among the utterances of the great philosopher-acharyas of Hinduism, or in any of Hinduism’s six main schools of philosophical thought (the Shad-darshanas). Throughout the history of the tradition, such great Hindu philosophers as Vyasa, Shankara, Ramanuja, Madhva, Vallabha, Vijnana Bhikshu, Swaminarayan (Sahajanand Swami) and others made unambiguous and unapologetic distinctions between the religion of Hinduism and non-Hindu religions. The sages of pre-modern Hinduism had no difficulty in boldly asserting what was, and what was not, to be considered Hindu. And they did so often! This lucid sense of religious community and philosophical clarity is seen first and foremost in the very question of what, precisely, constitutes a “Hindu.” Without knowing the answer to this most foundational of questions, it is impossible to fully assess the damaging inadequacies of Radical Universalist dogma.

Who is a Hindu?

Remarkably, when the question of who is a Hindu is discussed today, we get a multitude of confused and contradictory answers from both Hindu laypersons and from Hindu leaders. Some of the more simplistic answers to this question include: anyone born in India is automatically a Hindu (the ethnicity fallacy); if your parents are Hindu, then you are Hindu (the familial argument); if you are born into a certain caste, then you are Hindu (the genetic inheritance model); if you believe in reincarnation, then you are Hindu (forgetting that many non-Hindu religions share at least some of the beliefs of Hinduism); if you practice any religion originating from India, then you are a Hindu (the national origin fallacy). The real answer to this question has already been conclusively answered by the ancient sages of Hinduism.

The two primary factors that distinguish the individual uniqueness of the great world religious traditions are a) the scriptural authority upon which the tradition is based, and b) the fundamental religious tenets that it espouses. If we ask the question what is a Jew, for example, the answer is: someone who accepts the Torah as his scriptural guide and believes in the monotheistic concept of God espoused in these scriptures. What is a Christian? A person who accepts the Gospels as their scriptural guide and believes that Jesus is the incarnate God who died for their sins. What is a Muslim? Someone who accepts the Qur’an as their scriptural guide, and believes that there is no God but Allah, and that Mohammed is his prophet. In other words, what determines whether a person is a follower of any particular religion is whether or not they accept, and attempt to live by, the scriptural authority of that religion. This is no less true of Hinduism than it is of any other religion on Earth. Thus, the question of who is a Hindu is similarly easily answered.

By definition, a Hindu is an individual who accepts as authoritative the religious guidance of the Vedic scriptures, and who strives to live in accordance with Dharma, God’s divine laws as revealed in those Vedic scriptures. In keeping with this standard definition, all of the Hindu thinkers of the six traditional schools of Hindu philosophy (shad-darshanas) insisted on the acceptance of the scriptural authority (shabda-pramana) of the Vedas as the primary criterion for distinguishing a Hindu from a non-Hindu, as well as distinguishing overtly Hindu philosophical positions from non-Hindu ones.

It has been the historically accepted standard that if you accept the four Vedas and the smriti canon (one example of which would include the Mahabharata, Ramayana, Bhagavad Gita, Puranas, etc.) as your scriptural authority, and live your life in accordance with the dharmic principles of these scriptures, you are then a Hindu. Thus, any Indian who rejects the authority of the Vedas is obviously not a Hindu–regardless of his or her birth. While an American, Canadian, Russian, Brazilian, Indonesian or Indian who does accept the authority of the Vedas obviously is a Hindu. One is Hindu, not by race, but by belief and practice.

Clearly defining Hinduism

Traditional Hindu philosophers continually emphasized the crucial importance of clearly understanding what is Hinduism proper and what are non-Hindu religious paths. You cannot claim to be a Hindu, after all, if you do not understand what it is that you claim to believe, and what it is that others believe. One set of antonymous Sanskrit terms repeatedly employed by many traditional Hindu philosophers were the words vaidika and avaidika.

The word vaidika (or Vedic in English) means one who accepts the teachings of the Vedas. It refers specifically to the unique epistemological stance taken by the traditional schools of Hindu philosophy, known as shabda-pramana, or employing the divine sound current of Veda as a means of acquiring valid knowledge. In this sense the word vaidika is employed to differentiate those schools of Indian philosophy that accept the epistemological validity of the Vedas as apaurusheya–or a perfect authoritative spiritual source, eternal and untouched by the speculations of humanity–juxtaposed with the avaidika schools that do not ascribe such validity to the Vedas. In pre-Christian times, avaidika schools were clearly identified by Hindu authors as being specifically Buddhism, Jainism and the atheistic Charvaka school, all of whom did not accept the Vedas. These three schools were unanimously considered non-Vedic, and thus non-Hindu (they certainly are geographically Indian religions, but they are not theologically/philosophically Hindu religions).

Dharma Rakshaka: The defenders of Dharma

With the stark exception of very recent times, Hinduism has historically always been recognized as a separate and distinct religious phenomenon, as a tradition unto itself. It was recognized as such both by outside observers of Hinduism, as well as from within, by Hinduism’s greatest spiritual teachers. The saints and sages of Hinduism continuously strived to uphold the sanctity and gift of the Hindu worldview, often under the barrages of direct polemic opposition by non-Hindu traditions. Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Charvakins (atheists), the four main philosophical schools found in Indian history, would frequently engage each other in painstakingly precise debates, arguing compellingly over even the smallest conceptual minutia of philosophical subject matter. The sages of Hinduism met such philosophical challenges with cogent argument, rigid logic and sustained pride in their tradition, usually soundly defeating their philosophical opponents in open debate.

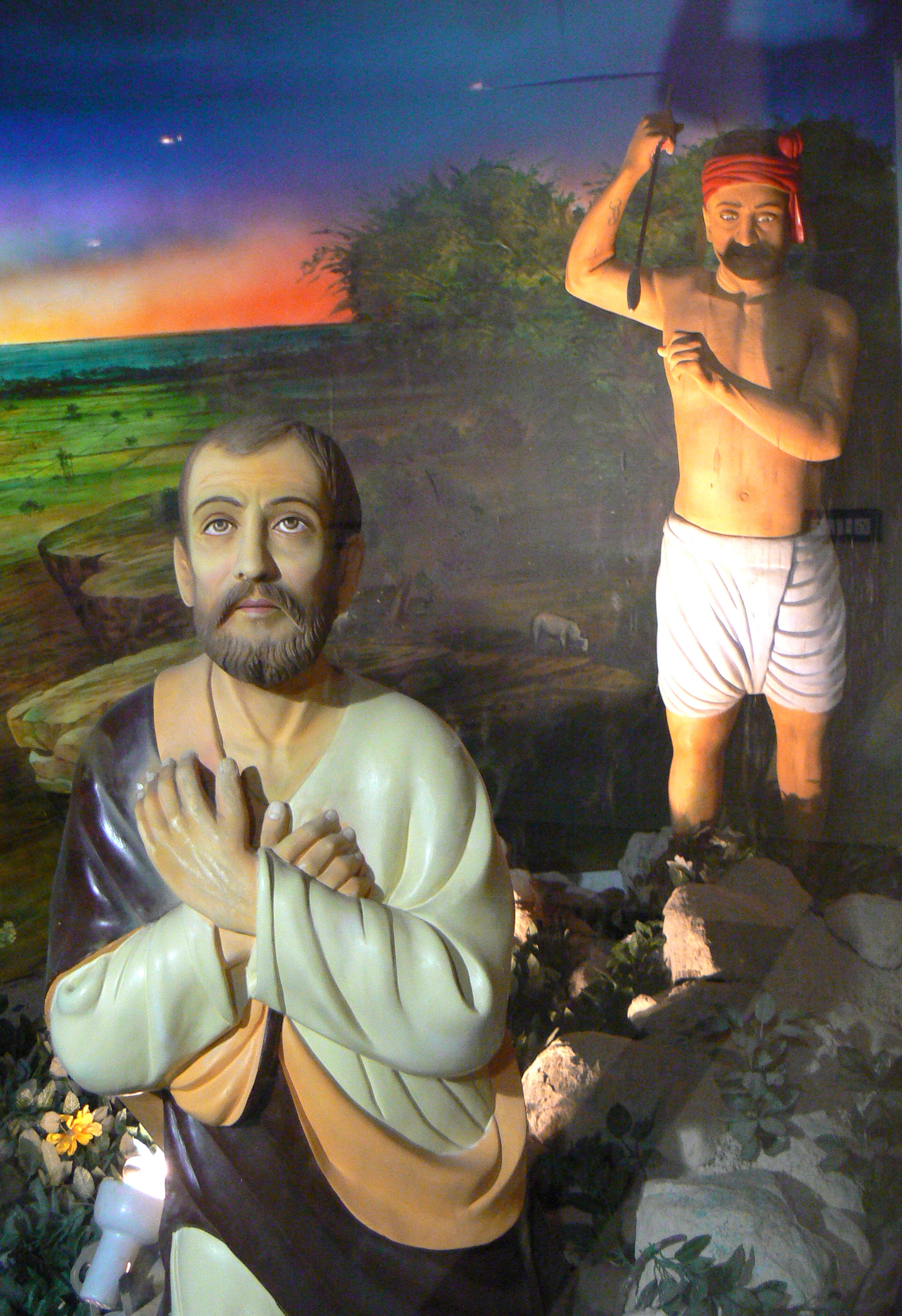

Adi Shankaracharya (788-820), as only one of many examples of Hindu acharyas defending their religion, earned the title “Digvijaya,” or “Conqueror of All Directions.” This title was awarded Shankara due solely to his formidable ability to defend the Hindu tradition from the philosophical incursions of opposing (purva-paksha), non-Hindu schools of thought. Indeed, Shankara is universally attributed, both by scholars and later, post-Shankaran Hindu leaders, with being partially responsible for the historical decline of Buddhism in India due to his intensely polemic missionary activities. No Radical Universalist was he!

The great teacher Madhva is similarly seen as being responsible for the sharp decline of Jainism in South India due to his immense debating skills in defense of Vaidika Dharma. Pre-modern Hindu sages and philosophers recognized and celebrated the singular vision that Hinduism has to offer the world, clearly distinguished between Hindu and non-Hindu religions, and defended Hinduism to the utmost of their prodigious intellectual and spiritual abilities. They did so unapologetically, professionally and courageously. The Hindu worldview only makes sense, has value and will survive if all Hindus similarly celebrate our religion’s uniqueness today.

Traditional Hinduism versus Neo-Hinduism

A tragic occurrence in the long history of Hinduism was witnessed throughout the 19th century, the destructive magnitude of which Hindu leaders and scholars today are only beginning to adequately assess and address. This development both altered and weakened Hinduism to such a tremendous degree that Hinduism has not yet even begun to recover. The classical, traditional Hinduism that had been responsible for the continuous development of thousands of years of sophisticated culture, architecture, music, philosophy, ritual and theology came under devastating assault during the 19th century British colonial rule like at no other time in India’s history. For a thousand years previous to the British Raj, foreign marauders had repeatedly attempted to destroy Hinduism through overt physical genocide and the systematic destruction of Hindu temples and sacred places. Traditional Hinduism’s wise sages and noble warriors had fought bravely to stem this anti-Hindu holocaust to the best of their ability, more often than not paying for their bravery with their lives.

What the Hindu community experienced under British Christian domination, however, was an ominously innovative form of cultural genocide. What they experienced was not an attempt at the physical annihilation of their culture, but a deceivingly more subtle program of intellectual and spiritual annihilation. It is easy for a people to understand the urgent threat posed by an enemy that seeks to literally kill them. It is much harder, though, to understand the insidious threat of an enemy who, while remaining just as deadly, claims to seek only to serve a subjugated people’s best interests.

During this short span of time in the 19th century, the ancient grandeur and beauty of a classical Hinduism that had stood the test of thousands of years came under direct ideological attack. What makes this period especially tragic is that the main apparatus that the British used in their attempts to destroy traditional Hinduism were the British-educated, spiritually co-opted sons and daughters of Hinduism itself. Seeing traditional Hinduism through the eyes of their British masters, a pandemic wave of 19th-century Anglicized Hindu intellectuals saw it as their solemn duty to “Westernize” and “modernize” traditional Hinduism to make it more palatable to their new European overlords. One of the phenomena that occurred during this historic period was the fabrication of a new movement known as “neo-Hinduism.” Neo-Hinduism was an artificial religious construct used as a paradigmatic juxtaposition to the legitimate traditional Hinduism that had been the religion and culture of the people for thousands of years. Neo-Hinduism was used as an effective weapon to replace authentic Hinduism with a British-invented version designed to make a subjugated people easier to manage and control.

The Christian and British inspired neo-Hindu movement attempted to execute several overlapping goals, and did so with great success:

A. the subtle Christianization of Hindu theology, which included concerted attacks on iconic imagery (murti), panentheism, and belief in the beloved Gods and Goddesses of traditional Hinduism;

B. the imposition of the Western scientific method, rationalism and skepticism on the study of Hinduism in order to show Hinduism’s supposedly inferior grasp of reality;

C. ongoing attacks against the ancient Hindu science of ritual in the name of simplification and democratization of worship;

D. the importation of Radical Universalism from liberal, Unitarian/Universalist Christianity as a device designed to severely water down traditional Hindu philosophy.

The dignity, strength and beauty of traditional Hinduism was recognized as the foremost threat to Christian European rule in India. The invention of neo-Hinduism was the response. Had this colonialist program been carried out with a British face, it would not have met with as much success as it did. Therefore, an Indian face was cleverly used to impose neo-Hinduism upon the Hindu people. The resultant effects of the activities of Indian neo-Hindus were ruinous for traditional Hinduism.

The primary dilemma with Hinduism as we find it today, in a nutshell, is precisely this problem of 1) not recognizing that there are really two distinct and conflicting Hinduisms today, neo-Hindu and traditionalist Hindu; and 2) traditionalists being the guardians of authentic Dharma philosophically and attitudinally, but not yet coming to full grips with the modern world–i.e., not yet having found a way of negotiating authentic Hindu Dharma with modernity in order to communicate the unadulterated Hindu Dharma in a way that the modern mind can fully appreciate it. Hinduism will continue to be a religion mired in confusion about its own true meaning and value until traditionalist Hindus can assertively, professionally and intelligently communicate the reality of genuine Hinduism to the world. Until they learn how to do this, neo-Hinduism will continue its destructive campaign.

The Non-Hindu origins of Radical Universalism

Radical Universalism is neither traditional nor classical. Its origins can be traced back to the early 19th century. It is an idea not older than two centuries. Its intellectual roots are not even to be found in Hinduism itself, but rather are clearly traced back to Christian missionary attempts to alter the genuine teachings of authentic Hinduism. Radical Universalism was in vogue among 19th century British-educated Indians, most of who had little accurate information about their own Hindu intellectual and spiritual heritage. These Westernized Indians were often overly eager to gain acceptance and respectability for Indian culture from a Christian European audience who saw in Hinduism nothing more than the childish prattle of a brutish, colonized people. Many exaggerated stereotypes about Hinduism had been unsettling impressionable European minds for a century previous to their era. Rather than attempting to refute these many stereotypes about Hinduism by presenting Hinduism in its authentic and pristine form, however, many of these 19th-century Christianized Indians felt it was necessary to instead gut Hinduism of anything that might seem offensively exotic to the European mind. Radical Universalism seemed to be the perfect base notion upon which to artificially construct a “new” Hinduism that would give the Anglicized 19th-century Indian intelligentsia the acceptability they so yearned to be granted by their British masters.

We encounter one of the first instances of the Radical Universalist infiltration of Hinduism in the syncretistic teachings of Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), the founder of the Brahmo Samaj. A highly controversial figure during his life, Roy was a Bengali intellectual who was heavily influenced by the teachings of the Unitarian Church, a heterodox denomination of Christianity. In addition to studying Christianity, Islam and Sanskrit, he studied Hebrew and Greek with the dream of translating the Bible into Bengali. A self-described Hindu “reformer,” he viewed Hinduism through a colonial Christian lens. The Christian missionaries had told Roy that traditional Hinduism was a barbaric religion that had led to oppression, superstition and ignorance of the Indian people. He believed them. More, Roy saw Biblical teachings, specifically, as holding the cherished key to altering traditional Hindu teachings to make them more acceptable to India’s colonial masters. In his missionary zeal to Christianize Hinduism, he even wrote an anti-Hindu tract known as The Precepts of Jesus: The Guide to Peace and Happiness. It was directly from these Christian missionaries that Roy derived the bulk of his ideas, including the anti-Hindu notion of the radical equality of all religions.

In addition to acquiring Radical Universalism from the Christian missionaries, Roy also felt it necessary to Christianize Hinduism by adopting many Biblical theological beliefs into his neo-Hindu “reform” movement. Some of these other non-intrinsic adaptations included a rejection of Hindu panentheism, to be substituted with a more Biblical notion of anthropomorphic monotheism; a rejection of all iconic worship ( “graven images” as the crypto-Christians of the Brahmo Samaj phrased it); and a repudiation of the doctrine of avataras, or the divine descent of God. Roy’s immediate successors, Debendranath Tagore and Keshub Chandra Sen, attempted to incorporate even more Christian ideals into this neo-Hinduism invention. The Brahmo Samaj is today extinct as an organization, but the global Hindu community is still feeling the damaging effects of its pernicious influence.

The next two neo-Hindu Radical Universalists that we witness in the history of 19th century Hinduism are Sri Ramakrishna (1836-1886) and Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902). Though Vivekananda was a disciple (shishya) of Ramakrishna, the two led very different lives. Ramakrishna was born into a Hindu family in Dakshineshwar. In his adult life, he was a Hindu temple priest and a fervently demonstrative devotee of the Divine Mother. His primary object of worship was the Goddess Kali, whom he worshiped with intense devotion all of his life. Despite his Hindu roots, however, many of Ramakrishna’s ideas and practices were derived, not from the ancient wisdom of classical Hinduism, but from the non-Vedic religious outlooks of Islam and liberal Christianity.

Though he saw himself as being primarily Hindu, Ramakrishna believed that all religions aimed at the same supreme destination. He experimented briefly with Muslim, Christian and a wide variety of Hindu practices, blending, mixing and matching practices and beliefs as they appealed to him at any given moment. In 1875, Ramakrishna met Keshub Chandra Sen, the then leader of the neo-Hindu Brahmo Samaj. Sen introduced Ramakrishna to the close-knit community of neo-Hindu activists who lived in Calcutta, and would in turn often bring these activists to Ramakrishna’s satsangas. Ramakrishna ended up being one of the most widely popular of neo-Hindu Radical Universalists.

Swami Vivekananda was arguably Ramakrishna’s most capable disciple. An eloquent and charismatic speaker, Vivekananda will be forever honored by the Hindu community for his brilliant defense of Hinduism at the Parliament of World Religions in 1893. Likewise, Vivekananda contributed greatly to the revival of interest in the study of Hindu scriptures and philosophy in turn-of-the-century India. The positive contributions of Vivekananda toward Hinduism are numerous and great indeed. Notwithstanding his remarkable undertakings, however, Vivekananda found himself in a similarly difficult position as other neo-Hindu leaders of his day were. How to make sense of the ancient ways of Hinduism, and hopefully preserve Hinduism, in the face of the overwhelming onslaught of modernity? Despite many positive contributions by Vivekananda and other neo-Hindus in attempting to formulate a Hindu response to the challenge of modernity, that response was often made at the expense of authentic Hindu teachings. Vivekananda, along with the other leaders of the neo-Hindu movement, felt it was necessary to both water down the Hinduism of their ancestors, and to adopt such foreign ideas as Radical Universalism, with the hope of gaining the approval of the European masters they found ruling over them.

While Ramakrishna led a contemplative life of relative isolation from the larger world, Swami Vivekananda was to become a celebrated figure on the world religion stage. Vivekananda frequently took a somewhat dismissive attitude to traditional Hinduism as it was practiced in his day, arguing (quite incorrectly) that Hinduism was too often irrational, overly mythologically oriented, and too divorced from the more practical need for social welfare work. He was not much interested in Ramakrishna’s earlier emphasis on mystical devotion and ecstatic worship. Rather, Vivekananda laid stress on the centrality of his own idiosyncratic and universalistic approach to Vedanta, what later came to be known as “neo-Vedanta.”

Vivekananda differed slightly with Ramakrishna’s version of Radical Universalism by attempting to superimpose a distinctly neo-Vedantic outlook on the idea of the unity of all religions. Vivekananda advocated a sort of hierarchical Radical Universalism that espoused the equality of all religions, while simultaneously claiming that all religions are really evolving from inferior notions of religiosity to a pinnacle mode. That pinnacle of all religious thought and practice was, for Vivekananda, of course, Hinduism. Though Vivekananda contributed a great deal toward helping European and American non-Hindus to understand the greatness of Hinduism, the Radical Universalist and neo-Hindu inaccuracies that he fostered have also done a great deal of harm as well.

In order to fully experience Hinduism in its most spiritually evocative and philosophically compelling form, we must learn to recognize, and reject, the concocted influences of neo-Hinduism that have permeated the mass of Hindu thought today. It is time to rid ourselves of the liberal, Christian-inspired reformism that so deeply prejudiced such individuals as Ram Mohan Roy over a century ago. We must free ourselves from the anti-Hindu dogma of Radical Universalism that has so weakened Hinduism, and re-embrace a classical form of Hinduism that is rooted in the actual scriptures of Hinduism, that has been preserved for thousands of years by the various disciplic successions of legitimate acharyas, and that has stood the test of time. We must celebrate traditional Hinduism. The neo-Hindu importation of Radical Universalism may resonate with many on a purely emotional level, but it remains patently anti-Hindu in its origins, an indefensible proposition philosophically, and a highly destructive doctrine to the further development of Hinduism.

“We’re not superior … therefore we’re superior”

In addition to demonstrating the non-Hindu nature of Radical Universalism from a historical and literary perspective, it is also important to examine the validity of the claims of Radical Universalism from an overtly philosophical perspective. We need to see if the idea that all religions are the same makes any objective rational sense at all. The problem that is created is that since only Hinduism is supposedly teaching the “truth” that all religions are the same, and since no other religion seems to be aware of this “truth” other than modern-day Hinduism, then Hinduism is naturally superior to all other religions in its exclusive possession of the knowledge that all religions are the same. In its attempt to insist that all religions are the same, Radical Universalism has employed a circular pattern of logic that sets itself up as being, astoundingly, superior to all other religions. Thus, attempting to uphold the claim of Radical Universalism leads to a situation in which Radical Universalism’s very claim is contradicted. A good way to see the inherent circular logic of this claim is to conduct a formal propositional analysis of the argument.

1. Modern Hinduism is the only religion that supports Radical Universalism.

2. Radical Universalism states that all religions are the same.

3. No other religion states or knows that all religions are the same.

4. Since a) no other religions know the truth that all religions are the same, and since b) only Hinduism knows the truth that all religions are the same, only Hinduism knows the truth of all religions.

5. Only Hinduism knows the truth of all religions.

6. Therefore, Hinduism is both distinct and superior to all religions.

7. Therefore, given Hinduism’s distinctness from and superiority to all religions: all religions are not the same.

8. Since all religions are not the same, Radical Universalism is untrue.

Hinduism: The empty mirror?

A further self-defeating aspect of Radical Universalism is that it severely negates the very need for Hinduism itself, relegating the Hindu tradition to merely being an ideological vehicle subservient to the Radical Universalist agenda, and rendering any meaningful sense of Hindu cultural and religious identity barren. If the Radical Universalists of neo-Hinduism claim that all religions are the same, then each and every religion is simultaneously deprived of all attributive uniqueness. They are deprived of their identity. This is manifestly true of Hinduism even more so than any other religion, since Radical Universalist neo-Hindus would be the sole representatives of Radical Universalism on the world religious stage today.

If we say that the ancient teachings and profoundly unique spiritual culture of Hinduism is qualitatively no better or no worse than any other religion, then what is the need for Hinduism? Hinduism then becomes the blank backdrop, the empty theatrical stage, upon which all other religious ideas are given the unbridled freedom to act, entertain and perform, all at the expense of Hinduism’s freedom to assert its own identity. Hinduism, subjugated to the Radical Universalist agenda, would find itself reduced to being merely an inert mirror, doomed to aspire to nothing more philosophically substantial than passively reflecting every other religious creed, dogma and practice in its universalist-imposed sheen.

Brahman and free volition

The primary reason why Radical Universalists claim that all religions are the same is found in the pretentious assumption that the various individual Absolutes toward which each religion aims are, unbeknownst to them all, really the same. In other words, the members of all other religions are also really seeking Brahman; they are just not intelligent enough to know it! As every other religion will vociferously affirm, however, they are not seeking Brahman. Brahman is not Allah; Allah is not Nirvana; Nirvana is not Kevala; Kevala is not polytheistic Gods/Goddesses; polytheistic Gods/Goddesses is not Yahweh; Yahweh is not the Ancestors; the Ancestors are not tree spirits; tree spirits are not Brahman. When a religious Muslim tells us that he is worshiping Allah, and not Brahman, we need to take him seriously and respect his choice. When a Buddhist tells us that he wants to achieve Nirvana, and not Brahman, we need to take his claim seriously and respect his decision; and so on. To disrespectfully insist that all other religions are really just worshiping Brahman without knowing it, and to do so in the very name of respect and tolerance, is the pinnacle of hypocrisy and intolerance. The uncomplicated fact is that, regardless of how sincerely we may wish that all religions desire the same Absolute that we Hindus wish to achieve, other religions simply do not. We need to accept and live with this concrete theological fact.

Distinguishing salvific states

The Christian’s ultimate aim in salvation is to be raised physically from the dead on the eschatological day of judgment, and to find herself in heaven with Jesus, who is to be found seated at the right hand of the anthropomorphic male Father/God of the Old and New Testament. Muslims aspire toward a delightfully earthy paradise in which 72 houris, or virgin youth, will be granted to them to enjoy (Qur’an, 76:19). Jains are seeking kevala, or aloneness, in which they will enjoy an eternal existence of omniscience and omnipotence without the unwanted intrusion of a God, a Brahman or an Allah. Buddhists seek to have all the transitory elements that produce the illusion of a self melt away, and to have themselves in turn melt away into the nihilism of nirvana. To the Buddhist, Brahman also is an illusion.

Each of these different religions has its own categorically unique concept of salvation and of the Absolute toward which its followers aspire. Each concept is irreconcilable with the others. To state the situation unequivocally, if a Christian, Muslim, Jain or Buddhist, upon achieving his distinct notion of salvation, were to find himself instead united with Brahman, he would most likely be quite upset and confused indeed. And he would have a right to be! Conversely, the average yogi probably would be quite bewildered upon finding 72 virgins waiting for him upon achieving moksha, rather than realizing the eternal bliss of Brahman. One person’s vision of salvation is another person’s idea of hell.

Reclaiming the Jewel of Dharma

Sanatana Dharma, authentic Hinduism, is a religion that is just as unique, valuable and integral a religion as any other major religion on Earth, with its own beliefs, traditions, advanced system of ethics, meaningful rituals, philosophy and theology. The religious tradition of Hinduism is solely responsible for the revelation of such concepts and practices as yoga, ayurveda, vastu, jyotisha, yajna, puja, tantra, Vedanta, karma, etc. These and countless other Vedic-inspired elements of Hinduism belong to Hinduism, and to Hinduism alone. They are also Hinduisam’s divine gift to a suffering world.

If we want to ensure that our youth remain committed to Hinduism as a meaningful path, that our leaders teach Hinduism in a manner that represents the tradition faithfully and with dignity, and that the greater Hindu community can feel that they have a religion that they can truly take pride in, then we must abandon Radical Universalism. If we want Hinduism to survive so that it may continue to bring hope, meaning and enlightenment to untold future generations, then the next time our son or daughter asks us what Hinduism is really all about, let us not slavishly repeat to them that all religions are the same. Let us instead look into their eyes, and teach them the uniquely precious, beautifully endearing, and philosophically profound truths of our tradition–truths that have been responsible for keeping Hinduism a vibrantly living religious force for over 5,000 years. Let us teach them Sanatana Dharma, the eternal way of Truth. – Hinduism Today, Hawaii, July/August/September 2005

› Dr. Frank Morales (Dharma Pravartika) is a teacher and lecturer on yoga spirituality, an ordained priest in the Vaishnava tradition, and founder of the American Institute for Yoga Studies. His commitment to Hindu thought and practice began at age 12. He has a PhD in Philosophy of Religion and Hindu Studies from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

› A downloadable edition of this essay is available on Scribd.